ATOM

An Atom: Building Blocks of the Universe is the smallest unit of matter that retains all the chemical properties of an element. Atoms are the fundamental building blocks of all ordinary matter.

🧪 Chemical Properties of Atom: Building Blocks of the Universe

Chemical properties describe how an atom interacts with other atoms to form compounds, primarily determined by the arrangement of its electrons, especially the valence electrons (those in the outermost shell).

Valency (Combining Capacity):

The number of chemical bonds an atom can typically form. It depends on the number of electrons in the outermost shell, as atoms tend to gain, lose, or share electrons to achieve a stable, full outer shell.

Valency = Electrons to lose, gain, or share to reach stability.

Ionization Energy:

The minimum energy required to remove one electron from a neutral atom in its gaseous state.

Electron Affinity:

The energy change that occurs when an electron is added to a neutral atom in its gaseous state.

Electronegativity:

The tendency of an atom to attract a shared pair of electrons when it is part of a chemical bond.

cop30-conference-of-parties-2025

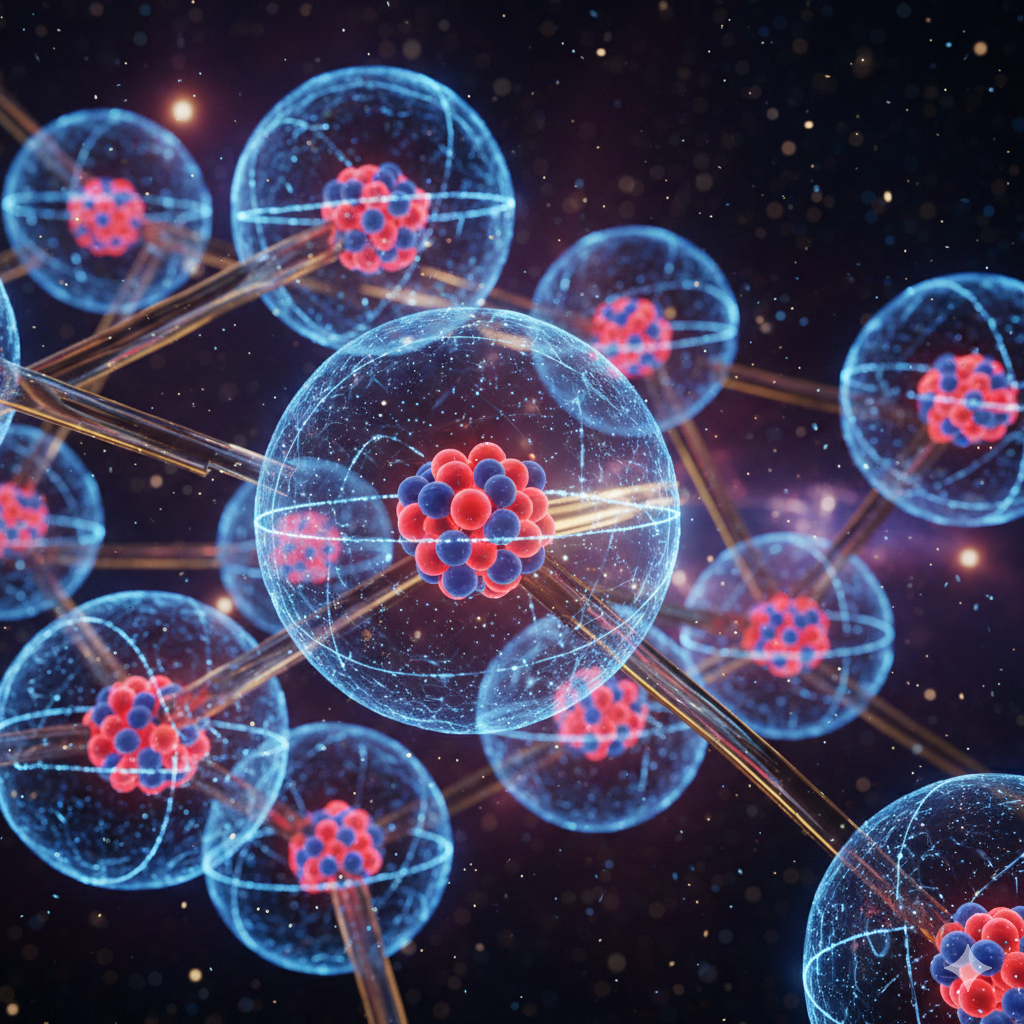

STRUCTURE OF ATOM:BUILDING BLOCK OF UNIVERSE

1. The Nucleus (The Center)

The dense, central part of the atom which contains the majority of the atom’s mass (over 99.9%).4 It consists of:

-

Protons (p+): Positively charged particles.6 The number of protons determines the element’s identity and is called the atomic number (Z).8

-

Neutrons (n-):10 Electrically neutral particles (no charge).11 Atoms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons; these variations are called isotopes.

2. The Electron Cloud (The Outer Region)

The electron cloud is the space surrounding the nucleus where electrons are found. This region accounts for most of the atom’s volume (greater than 99\%) but very little of its mass.

-

Electrons orbit the nucleus in specific energy levels or shells.

-

They are bound to the nucleus by the electromagnetic force (the attraction between the negative electrons and the positive protons).

-

In a neutral atom, the number of electrons equals the number of protons (e^- = p^+), making the atom electrically neutral overall.

3.Charge and Stability

-

In a neutral atom, the number of protons (positive charge) is equal to the number of electrons (negative charge), making the net charge of the atom zero.

-

The positive nucleus is held together by the strong nuclear force, which overcomes the repulsion between the positively charged protons.

-

The negative electrons are attracted to the positive nucleus by the electromagnetic force, which keeps them orbiting the center.

-

-

📜 History of Atom: Building Blocks of the Universe

The Philosophical Genesis (Antiquity)

The atomic paradigm was first articulated as a philosophical atomism in ancient Greece.1 The term atom itself is derived from the Greek word atomos signifying uncuttable or indivisible.3

-

Leucippus and Democritus (5th Century BCE): These Greek thinkers posited that nature comprised two essential principles: atoms and the void.4 Democritus, in particular, postulated that all macroscopic phenomena result from the mechanical collision and conglomeration of these infinitesimal, indestructible, and immutable units, which vary only in shape, arrangement, and magnitude.5 This model, however, was purely a matter of rational speculation, lacking any empirical corroboration, and was ultimately eclipsed for centuries by the continuous matter model championed by Aristotle

The Empirical Resurgence (Early 19th Century)

The transition from a purely speculative concept to a rigorous scientific theory occurred in the early 19th century through the meticulous work of John Dalton.

-

-

John Dalton (1803-1808): Dalton resurrected the term atom to denote the discrete units of a chemical element. His atomic theory was predicated upon chemical experimentation and quantitative laws:

-

Law of Conservation of Mass (Lavoisier): Atoms cannot be created or annihilated in a chemical transformation.

-

Law of Definite Proportions (Proust): A given chemical compound invariably contains its constituent elements in fixed, unvarying mass proportions.

-

Law of Multiple Proportions (Dalton): When two elements combine to form more than one compound, the ratios of the masses of the second element that combine with a fixed mass of the first element are ratios of small whole numbers

-

-

Dalton’s model conceptualized the atom as a solid, homogeneous, indivisible sphere—the ultimate particle of an element, defining the era of modern chemistry.

The Elucidation of Subatomic Structure (Late 19th & Early 20th Century)

Subsequent epochal discoveries irrevocably dismantled the postulate of atomic indivisibility, initiating the delineation of subatomic architecture.

| Scientist (Year) | Model/Discovery | Description |

| J.J. Thomson (1897/1904) | Electron/Plum Pudding Model |

the plum pudding

The discovery of the negatively charged electron (e-) demonstrated the atom’s divisibility. The “Plum Pudding” model envisioned the atom as a positively charged, monolithic sphere with diminutive, negative electrons interspersed throughout.| Ernest Rutherford (1911) | Nuclear Model|

The Gold Foil Experiment irrevocably refuted the Plum Pudding model. Rutherford deduced that the atom is constituted primarily of vacuous space, possessing a minute, exceedingly dense, and positively charged nucleus at its geometric center, orbited by electrons.| Niels Bohr (1913) | Planetary/Shell Model|

To mitigate the instability predicted by classical electrodynamics (that orbiting electrons should spiral into the nucleus), Bohr invoked quantum principles. He postulated that electrons occupy only specific, quantized, non-radiating orbits or energy levels (shells).15 Transitions between these discrete orbits necessitate the absorption or emission of energy packets (quanta).

James Chadwick (1932) | Neutron (n) | Chadwick’s discovery of the electrically neutral neutron in the nucleus finalized the triad of fundamental subatomic particles, resolving the issue of mass discrepancy within the nucleus.

IV. The Quantum Mechanical Synthesis (Mid-20th Century to Present)

The contemporary understanding of the atom is underpinned by the Quantum Mechanical Model, which is far more mathematically intricate and probabilistic.

-

-

-

Schrödinger, Heisenberg, et al. (1926): This paradigm supplanted the deterministic, circular orbits of the Bohr model with electron orbitals.19 These are not fixed paths but rather three-dimensional probability distributions that express the likelihood of locating an electron within a particular region of space around the nucleus.20 This abstract, highly predictive model provides the comprehensive theoretical scaffolding for modern chemistry and physics.

-

-

Periodic table

The periodic table is an organized arrangement of all known elements that reflects and allows prediction of their atomic structure and chemical behavior.

Periodic Table Organization

The layout of the modern periodic table is directly based on the atomic number and the electron configuration of the elements.7

Periods (Rows)

-

The seven horizontal rows are called periods.8

-

The period number an element is in corresponds to the highest occupied main electron shell (principal quantum number, 9n) in its ground state electron configuration.10

-

Moving across a period from left to right, the atomic number increases by one, meaning one proton and one electron are added, and the electrons are filling the same main energy level.11

Groups (Columns)

-

The 18 vertical columns are called groups (or families).12

-

Elements in the same group share similar chemical properties because they generally have the same number of valence electrons and, therefore, similar outermost electron shell configurations.13

-

For example, all elements in Group 1 (Alkali Metals) have one valence electron and are highly reactive.14

-

Group 18 elements (Noble Gases) have a full outermost shell (usually eight valence electrons, satisfying the octet rule), making them highly stable and unreactive.15

-

Blocks

The periodic table can be divided into blocks based on the type of subshell (16s, p, d, f) being filled by the valence electrons:17

-

s-block: Groups 1 and 2 (and Helium).

-

p-block: Groups 13 through 18.

-

d-block: Groups 3 through 12 (Transition Metals).

-

f-block: Lanthanides and Actinides (Inner Transition Metals).18